- Home

- Jagmeet Singh

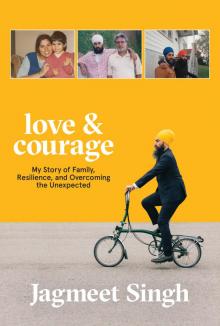

Love & Courage

Love & Courage Read online

Contents

Dedication

Prologue: Love & Courage

Part One

1: A New World

2: Chardi Kala—Rising Spirits

3: Immigrant Ambition

4: Say It to My Face

5: Kicks and Punches

Part Two

6: Point System

7: The Land of Five Rivers

8: The Russian Prince

9: Disputed Road

10: Role Reversal

Part Three

11: Bond between Brothers

12: A Need for Justice

13: A Different Kind of Fight

14: A Place to Call Home

15: To Walk a Better Path

16: Lottery Ticket

17: For the Betterment of All People

Epilogue: Leadership Convention—October 1, 2017

Acknowledgements

About the Author

To my family

Prologue

LOVE & COURAGE

Four months had passed since I’d made one of the biggest decisions of my life. I was running to become the eighth leader of one of Canada’s largest political parties, the New Democratic Party. From the moment I announced my candidacy, I had been riding a wave of life-changing events, and on that particular day in September, there was another one in store for me.

It was a beautiful day—the kind when summer hasn’t lost its hold and the weather seems to ignore that fall is just around the corner. I was heading to an event at Professor’s Lake Recreation Centre in Brampton, Ontario. As I drove through the surrounding neighbourhoods, I looked out my window and took in the buildings where I’d held countless community events over the years, each one bringing together hundreds of constituents who made up one of Canada’s most diverse communities. This was the riding I had represented for the past six years in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. The riding where my team and I had launched my leadership campaign.

Back then, in May 2017, pollsters gave us single-digit odds of winning. Analysts said I was too unknown, too inexperienced, too unrelatable. Columnists pointed to my turban and beard, and pondered whether a very visible minority could connect with all of Canada.

The past few months had been a blur of activity. In order to build the movement and create countrywide energy and excitement, we were holding events we playfully called “JagMeet and Greets” in communities as widespread as Duncan, BC, and Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. By that September day, my squad had signed up 47,000 new members—more than all the other NDP candidates combined. Our dream—to excite and invite a new generation of social democrats who believed in an inclusive Canada—was taking shape.

I felt my excitement building as I pulled into the park entrance and headed toward the recreation centre. We’d held events across the country, but this was the first official campaign stop in the city where it all started. Hosting an event in Brampton felt more like a homecoming party than another campaign stop. Behind the building’s vine-covered glass walls, hundreds of our original supporters and volunteers, friends who’d been with me since the beginning, were ready to celebrate.

I glanced at my watch, a gift from my bapu-ji—my dad—on my sixteenth birthday, and saw that it was time to get inside. A volunteer in an orange T-shirt was waiting for me at the front. I turned the volume down on Post Malone’s “Congratulations”—its contagious bravado and my non-stop playing of it made it our campaign’s unofficial anthem—and rolled down the window. Before I could ask, he said, “Don’t worry, I’ll park it.”

As he came around to the driver’s side, I adjusted my bright yellow turban in the rear-view mirror. I hopped out of the car and hustled up the concrete stairs toward the rec centre doors. Before I reached them, though, a woman in a black T-shirt stopped me.

“Oh, hey,” she said, casually puffing a cigarette. “Are you headed upstairs?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Can we ask you questions?”

“Now?”

“No, during the event.”

“Yes, you’ll be able to ask questions.”

“Okay,” she said, and stepped aside.

As soon as I got inside, Hannah Iland, my campaign tour director, spotted me and escorted me to the ballroom. “Heads up,” she said, “there’s a local TV station that wants to broadcast the speech so we need you to carry two mics.” She led me to the doorway. “We’ll announce you in a few seconds,” she said.

I peeked over her shoulder and scoped out a room filled with the bright faces of so many loved ones, and people who I had grown to know well over the past six years as a politician. I also caught a glance of the emcee, Gurkiran Kaur, the woman I was going to ask to marry me as soon as this crazy campaign was over. Hearing her introduce me to my supporters made the moment—and our future plans—all the more special.

When I walked onstage, the applause was overwhelming. Gurkiran handed me the two microphones with the signature affectionate look she gives me—a twinkle in her eye, a wink without winking. While trying to keep our relationship private so as not to cause any distractions from the campaign, we’d perfected our own sign language, a way of exchanging positive vibes without being overt about it.

I returned her glance and tested the mics on the crowd. “Wow, this is amazing,” I said, taking a moment to try to pick out my parents in the crowd of a hundred. “First question, does my voice carry better this way, or—”

“It carries great,” called a voice too clear to be from the crowd. I looked to my right and noticed the same woman who’d stopped me outside. She was striding over so quickly that her pace and proximity to me took me aback. As she spoke, her hands waved wildly and her head jerked from side to side. Her stream of words poured so fast I had a hard time grasping them.

“Hi, my name’s Jennifer, I asked about a questions process, there isn’t one, so I’m asking you now—”

“Hold on, one second, hold on,” I said, squeezing out the words between hers. I turned to the audience and tested the microphones again so that I could figure out what Jennifer wanted.

She stepped closer, head tilted, angrily pointing up and down. “We know you’re in bed with sharia,” she said.

Of course, I thought. This wasn’t the first time in my life I had been confronted with Islamophobia, or suggestions that there was something wrong with me because of the way I looked, or fears that I was a terrorist or terrorist-sympathizer.

“When is your sharia going to end?” she asked, wagging a finger in my face.

I’d encountered hecklers like Jennifer (many of whom were worse) throughout my life. In fact, several months earlier, the media scrum for our campaign launch had been delayed by a similar incident.

In that moment, I purposely didn’t explain to Jennifer that I’m Sikh, not Muslim. Though I’m proud of who I am, throughout my life, whenever I’ve been faced with Islamophobia, my answer has never been “I’m not a Muslim,” because hate is wrong, no matter who it’s aimed at. When it comes to stopping fear and division, all of us, no matter who we are, have to stand together. History has shown that if you allow any sort of hate to take hold, it spreads like fire, burning people for their race, gender, economic status, or sexuality.

Jennifer kept ranting. “We know you’re in bed with the Muslim Brotherhood. We know by your votes,” she yelled, still inches from my face. She disparaged Muslims and me, associated me with Islamic extremism, and said I didn’t support women’s rights, growing increasingly hostile with each new accusation.

I wasn’t worried for my safety—much of my life has been spent disarming aggressive people, and I’ve gotten pretty good at it—but I was worried that she’d ruin our celebration. So many people on my team had worked countless hours behind

the scenes, in offices, and on doorsteps, but hadn’t had a chance to come to our gatherings before that day. They and the many other supporters in the room deserved better than having their optimism derailed and drowned out by bigotry. I feared they’d walk away with a bitter taste in their mouths.

I knew I had to cool Jennifer down and respond in a way that made the room feel positive again, but the chances of turning it around slimmed with every second she seethed. When two campaign volunteers approached Jennifer and tried to shepherd her away, one of them gently touched her back. Jennifer spun around and snapped at him. “Don’t touch me!” she screamed. “Don’t anybody touch me, or I will contact the police immediately.”

There were rows of phone cameras pointed at us now. Great, I thought, YouTube’s about to blow up with an angry white woman shouting down a turbaned, bearded politician and threatening to call the police. I could sense the audience’s unrest, too, and I began to worry for Jennifer; I feared someone in the audience might direct their impatience or anger at her. I didn’t want that negativity to dictate the day. I wanted us all to remember why we were there, why we were doing this.

The reason was spelled out in two languages on orange signs all around me, but it didn’t sink in until I caught the eye of my bebey-ji—my mom—in the crowd. She looked at me with that calm wisdom that’s always there. I could see just a hint of encouragement, too. Suddenly, I remembered the lesson she’d repeated so many times to me: “Beta”—dear—“we are all one. We are all connected.”

Thanks to my mom, the right words finally came to me. “What do we believe in?” I asked the room. “We believe in love and courage, right? Love and courage!”

A dear friend of mine who runs a creative agency had helped develop “Love and Courage” for the campaign, but to me, it was more than just a slogan. When my friend presented the idea to me, I felt those two terms captured more than just my motivation, more than just my journey—they perfectly encapsulated the lessons life taught me, my values, who I am, and the way I try to live my life.

“Love and courage.” I repeated it until the crowd echoed the message louder than I could with the microphones. They chanted and clapped so powerfully that it seemed to surprise the heckler, who spun around with her arms up, cheering along. Did she not understand why the room was chanting?

“We believe in love and courage,” I said to everyone. “We believe in an inclusive Canada where no one’s left behind.”

It was in that moment that I finally looked Jennifer in the eyes. She wasn’t intimidating or scary at all. She was just a fellow human, one who maybe had been hurt or had faced hardships, or for whatever reason had grown resentful of people who looked different from her. When I saw that, I wanted her to know that I loved her. That we loved her. That we welcomed her and that she belonged in our version of Canada, too.

“As Canadians, do we believe in celebrating all diversity?” I asked the audience. “Give a round of applause for all diversity.” As the crowd applauded, I felt truly blessed that our supporters were living our campaign message, rather than just putting it on signs and in hashtags.

I was proud that everyone in the room had met hate with love. It was the courageous thing to do.

While Jennifer went on about my fictional ties to extremism, I countered with, “We welcome you. We love you. We support you, and we love you. Everyone in this room loves you, we all support you, we believe in your rights.”

In the days and weeks following the incident, many people asked how I remained calm in the face of so much aggression. My answer was always the same: Think about all the people who feel like they don’t belong. In my case, I was set apart by my beard, brown skin, turban, and a different-sounding name, but it might be the clothes you wear or the accent you speak with or how much you or your parents earn. When you feel like you don’t belong, you can become like Jennifer, or you can come up with positive ways to disarm prejudice.

After reflecting, I realized that people were really asking me where my love and courage in the face of hate came from. And that was a more complex question to answer.

Sometimes, loving someone, even yourself, takes a lot of courage. There isn’t a single moment when I realized that. Rather, it was a lesson I learned and relearned my entire life, sometimes the hard way.

My story is a Canadian story, a journey in a country where people who are as different from each other as me and Jennifer can both find our place. It’s a story of my family and the ups and downs we faced together. Some parts of it are hard to tell and could be hard for some to read. But most of all, this is a story filled with love and courage, and how I came to understand that these two forces are inextricably connected.

Part One

Chapter One

A NEW WORLD

My parents had to make a lot of tough decisions to give my siblings and me the life they thought we deserved. One of the hardest was saying goodbye when I was just a year old.

In the late 1970s, my parents, Jagtaran, “One Who Uplifts the World,” and Harmeet, “Friend to the Infinite Divine,” were living in a one-bedroom apartment in Scarborough, at the east end of Toronto. While Toronto was on track to becoming one of the most multicultural cities in the world, it sure didn’t seem like it at the time. Sometimes, in the elevator or on the bus, my parents would see another minority. But most of the time, my parents felt that they always stood out.

To help themselves feel at home, my parents sought comfort in the food of their childhood. The apartment was often filled with the fragrance of coriander, cumin, turmeric, and cloves from the dishes my mother made. That fragrance would follow us for the rest of my family’s lives together, through half a dozen homes and five cities. But back then, while they marvelled at the cleanliness and amenities of their apartment, they couldn’t imagine building a family in its cramped quarters, with only a single bedroom.

My parents, like many new Canadians, had found the transition to Canada from Panjab in 1976 difficult. It probably didn’t help that Canada effectively recognized none of their education or international experience. They were getting by on my mom’s meagre salary as my dad tried to pass the medical exam that would allow him to practise as a doctor in Canada. They each worked hours upon hours each day, trying to get ahead in their adopted country so that they could settle down and, hopefully, start a family.

Despite their precarious financial situation, my father was anxious to have children sooner rather than later.

“We’ve been married a year. What’s the hurry?” my mom asked. But this, she knew, was my father’s nature. He was always trying to dream bigger. He always wanted to provide more for his family; he was driven. He never wanted to settle. In a way this was the polar opposite to my mom, who was almost always content. She might be the only woman on earth to describe her labour and delivery as “not that bad.”

I was born on January 2, 1979, a sizeable nine pounds and five ounces. (Seriously, Mom? “Not that bad”?) My mom named me by combining both my parents’ names: the jag, pronounced “jug” (the world) from my dad’s name, Jagtaran, and meet (friend) from my mom’s name, Harmeet, meaning “friend to the world.”

For the first months of my life, I slept on a stack of blankets by my parents’ bed. Although we didn’t have a lot of money, I never wanted for the important things—food, warmth, love. Still, my parents wanted their children to more than survive—they wanted us to thrive.

So in the winter of 1980, as I was learning to take my first tentative steps, my parents took a leap of their own. My dad had applied to universities from one end of Canada to the other for his residency, flying between provinces for interviews. The travel was costly enough as it was, and my mom’s maternity leave had long since expired. They couldn’t afford a babysitter, so my grandfather came from Panjab to help look after me.

There was a lot of uncertainty about where my family would end up, so my dad suggested to my mom that my grandfather take me to live in Panjab for however long it took for m

y parents to get settled. It wasn’t unusual in Panjabi culture for grandparents to raise a child while the parents got established, but there would be eleven thousand kilometres between my mom and me, her first baby. The thought of being away from her beta for a week, let alone indefinitely, made her heart heavy. But she also knew I would be better off living in one place with my grandparents until my parents were more settled.

So, in late 1980, my mom kissed me goodbye and sent me to the airport in a taxi with my grandfather. As the car drove farther away from their apartment, she could feel a hole open up in her heart and grow with every mile between us.

“I never knew it would be that hard,” she said later. “I was broken.”

I had barely had time to get to know my home in Canada. But as my name said, I was a friend to the world, and I was about to learn just how big that world was.

My first years in Panjab are impossible for me to remember. But I often wonder if they left some unconscious imprint on me, some deeper sense of what my parents’ lives were like before they came to Canada.

My parents were born in Panjab, which literally translates to “five rivers”: panj, meaning five, and ab, meaning river. The region stretches across the plains just south of the Himalayan mountain range and is surrounded by China and Afghanistan. It was the frontier land through which ancient travellers typically made their way into the South Asian subcontinent. It was home to the first Sikh kingdom, created in the early nineteenth century by Maharaja Ranjit Singh, a leader renowned for his belief in pluralism and diversity. Sikhs made up less than 10 per cent of the population of that first Sikh kingdom, but because the realm was based on Sikh principles of equality and pluralism, all spiritual traditions, faiths, and religions had equal rights and held positions of power in the royal court and army.

The Sikh kingdom was the last territory to succumb to the British colonialism that swept across the South Asian subcontinent. Eventually, though, Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s kingdom did fall to the British in 1849 as a result of treachery and deceit, as opposed to military defeat. The ensuing century of British rule forced the hundreds of distinct and proud kingdoms across the subcontinent to amalgamate.

Love & Courage

Love & Courage